Phrenology and Physiognomy

"Extreme Despair and Rage mixed with Fear" (http://psychology.wikia.com/wiki/Physiognomy)

Phrenology and physiognomy are closely interconnected and played an important role in many of Edgar Allan Poe's stories. Phrenology explores the connection between the dimensions of the skull and certain personality characteristics, while physiognomy addresses an implicit relationship between a person's outward appearance and their personality. While considered scientific to an extent during the early 19th century, by 1843 both phrenology and physiognomy began to be referred to as pseudosciences by experiemental physiologists like Francois Magendie.

"Phrenology, a pseudo-science of the present day; like astrology, necromancy, and alchemy of former times, it pretends to localize in the brain the different kinds of memory. But its efforts are mere assertions..." (Magendie, 150)

"Phrenology, a pseudo-science of the present day; like astrology, necromancy, and alchemy of former times, it pretends to localize in the brain the different kinds of memory. But its efforts are mere assertions..." (Magendie, 150)

Origins of Phrenology

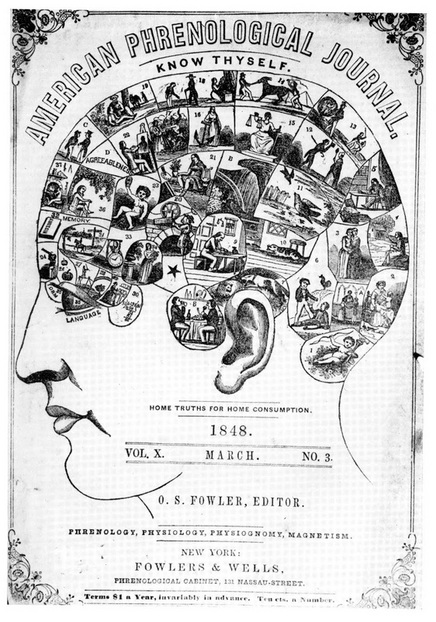

A cover of the American Phrenological Journal ("Phrenology, Then and Now")

Phrenology was originally developed by the German physician Franz Joseph Gall in 1796 and then elaborated upon by his associate Johann Spurzheim after 1825. The main basic tenets were as follows:

1. The organ of one's mind is the brain.

2. The mind is composed of multiple functional areas.

3. Each distinct area must have a corresponding spot or organ in the brain.

4. The size of a "brain organ" is representative of its dominance over others.

5. The shape of the brain is determined by the development of these various organs.

6. Since the skull reflects the shape of the brain, the skull can be read as an accurate index of psychological aptitudes and tendencies.

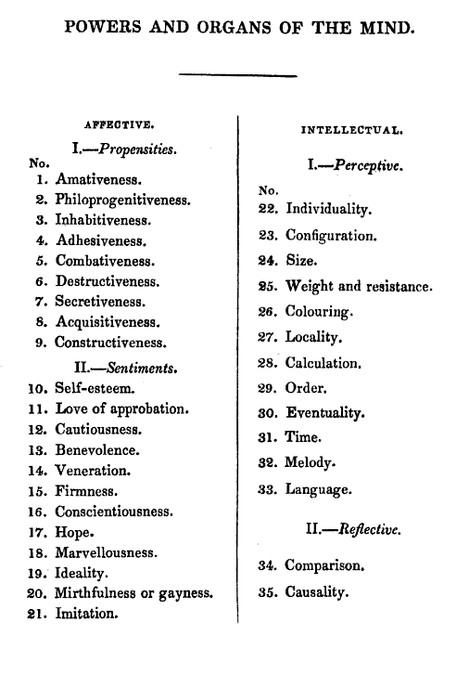

A phrenologist during their time therefore would assess a patients temperament by feeling and measuring as many as 27 different "brain organs", all of which were outlined by Gall. As the psuedo-science developed, diagnoses would eventually become a popular form of analysis when interviewing job applicants or assessing possible partners in a relationship. Phrenology was also seen as an accurate predictor of the future life of one's child. Gall's close collaborator, Johann Spurzheim, is especially known for popularizing phrenology around England, France and the United State through his many essays and lectures. Spurzheim also continued to build upon Gall's work, organizing the characteristics previously outlined by Gall into a hierarchical system.

1. The organ of one's mind is the brain.

2. The mind is composed of multiple functional areas.

3. Each distinct area must have a corresponding spot or organ in the brain.

4. The size of a "brain organ" is representative of its dominance over others.

5. The shape of the brain is determined by the development of these various organs.

6. Since the skull reflects the shape of the brain, the skull can be read as an accurate index of psychological aptitudes and tendencies.

A phrenologist during their time therefore would assess a patients temperament by feeling and measuring as many as 27 different "brain organs", all of which were outlined by Gall. As the psuedo-science developed, diagnoses would eventually become a popular form of analysis when interviewing job applicants or assessing possible partners in a relationship. Phrenology was also seen as an accurate predictor of the future life of one's child. Gall's close collaborator, Johann Spurzheim, is especially known for popularizing phrenology around England, France and the United State through his many essays and lectures. Spurzheim also continued to build upon Gall's work, organizing the characteristics previously outlined by Gall into a hierarchical system.

Origins of Physiognomy

The origins of physiognomy can be traced much further than phrenology, as several of physiognomy's assumptions formed the basis for phrenology. Physiognomy was first addressed in ancient Greece when philosophers such as Aristotle began inferring an innate connection between the outer body and inner characteristics. Over the course of human history these relations from physiognomy have influenced many social processes, relations, and conflicts. Physiognomy eventually fell into disrepute in the Middle Ages, during which mountebanks swindled gamblers and the gullible public with less scholastic practices and analyses. Modern revivals of the study of physiognomy have began again due to an increased, factual understanding of the individuals psychology and the ability of researchers to more properly categorize physical features and create similar, though much more subtle connections.

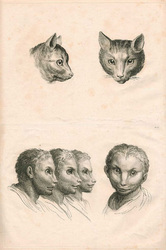

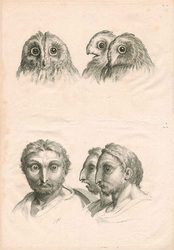

Plates from "Le Brun's System on Physiognomy."

Interpretations of a cat-like, owl-like and wolf-like relationship. (Morel D'Arleux)

Excerpt from Aristotle's "Prior Analytics"

It is possible to infer character from features, if it is granted that the body and the soul are changed together by the natural affections: I say ‘natural’, for though perhaps by learning music a man has made some change in his soul, this is not one of those affections which are natural to us; rather I refer to passions and desires when I speak of natural emotions. If then this were granted and also that for each change there is a corresponding sign, and we could state the affection and sign proper to each kind of animal, we shall be able to infer character from features. For if there is an affection which belongs properly to an individual kind, e.g. courage to lions, it is necessary that there should be a sign of it: for ex hypothesi body and soul are affected together. Suppose this sign is the possession of large extremities: this may belong to other kinds also though not universally. For the sign is proper in the sense stated, because the affection is proper to the whole kind, though not proper to it alone, according to our usual manner of speaking. The same thing then will be found in another kind, and man may be brave, and some other kinds of animal as well. They will then have the sign: for ex hypothesi there is one sign corresponding to each affection. (Aristotle, 2.27)

Connections with Poe

Physiognomy and phrenology were undergoing a societal revival during the period in which Edgar Allan Poe wrote many of his stories. As a result, Poe provided many physical descriptions to his readers in his texts as a way of emphasizing the supposedly innate connection between one's disposition and their personality. This fascinated readers, especially since many of the characters created by Poe often exemplified unstable mental conditions and other exaggerations of different personalities. Although there are hints towards the connection between the physical and the mental in almost all of Poe's works, "Ligeia" and "The Man of the Crowd" could be considered more directly associate with the sciences.

Ligeia

In Ligeia, Poe's narrator describes the qualities of Ligeia and his relationship with her. He describes her as having an "exquisite beauty", providing further details throughout such as her "contour of the lofty and pale forehead - it was faultless". The narrator extrapolates portions of her character through these physical attributes, such as her extensive knowledge in poetry, classical tongues, moral science, physical science and mathematics. Ligeia eventually passes away and the narrator marries again to a Lady Rowena. The story concludes with the transformation of Rowena into Ligeia following Rowena's death, possibly due to Ligeia's spirit and mind being embodied in her lengthily-detailed bedroom.

Man of the Crowd

"The Man of the Crowd" follows a nameless narrator who is fascinated by the crowds of people hurriedly running around outside a coffee shop. He proceeds to focus on a "decrepit old man" who is some sixty or seventy years old. The narrator follows the man attempting to determine how to classify him, only to arrive at the conclusion that he must be a man of deep crime due to his inability to remove himself from a crowd. This text relies more on physiognomy, and assumptions about a persons lifestyle or character due to their outward appearance. This is reinforced by descriptions of noblemen, merchants, attorneys, tradesmen, stock-jobbers, gentry, criminals, the poor and so on and so forth.

Informative Links

http://www.historyofphrenology.org.uk/ - contains references to the original works of Franz Joseph Gall

Free Google Books:

(Phrenology)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=d-gGAAAAQAAJ - Spurzheim (1825)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=dKBbAAAAQAAJ - Spurzheim (1829)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=hXAAAAAAMAAJ - Combe (1822)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=cdw_iM4pvQkC - Combe (1830)

(Physiognomy)

http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/a/aristotle/a8pra/ - Aristotle

For other cited texts, please refer to the "Works Cited" tab.

Free Google Books:

(Phrenology)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=d-gGAAAAQAAJ - Spurzheim (1825)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=dKBbAAAAQAAJ - Spurzheim (1829)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=hXAAAAAAMAAJ - Combe (1822)

http://books.google.com/ebooks?id=cdw_iM4pvQkC - Combe (1830)

(Physiognomy)

http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/a/aristotle/a8pra/ - Aristotle

For other cited texts, please refer to the "Works Cited" tab.